With Golden Week just beginning, Kanako and I set out on a long train and bus journey from Osaka to the southwestern tip of Fukushima prefecture for my first post-op Hyakumeizan. Would the weather gods be kind to us, and more importantly, would the new ticker hold up?

We arrived at the trailhead a little before 4pm, and immediately headed towards a lovely minshuku a short walk away. The kind couple showed us to our room and served up some local delicacies for dinner, including a local dish called sanshou uo, which I assumed was some sort of deep fried fish dipped in sanshou pepper. More on that later.

Early the next morning, we started up the deserted forest road to the start of the trailhead. The sun was shining brightly, and we had a simple plan: climb to the summit and stay in the emergency hut. Yuuki would take the first train from Tokyo and join us at the hut around dusk. The large wooden staircase at the start of the trail was free from snow, but we ran into the white stuff another 20 minutes up the steep spur, and quickly put on our crampons (and sunglasses). Kanako and I took a leisurely pace, since we had all day and didn’t want to risk any careless slips.

The beech forest has definitely seen better days. Victim to countless vandals who’d carelessly carved their initials into the precious bark, it brought to mind the recent defacing of the World Heritage trees in the Shirakami Mountains. We tried to keep our spirits up, instead focusing on the spendid play of light and shadow on the slowly retreating snow. Occasionally a skier would swoosh down from high above, enjoying the last clean runs of a dwindling snow season. Higher and higher we traversed, as the soft, fair weather clouds gently moved in from the west. Mt. Hiuchi stared at us across the valley, our target in two days time. We wondered if Yuuki would be able to catch up with us before we reached the hut.

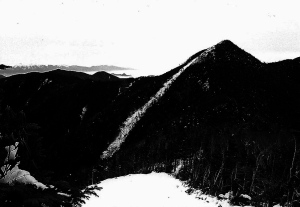

The forest seemed to go on forever, but the other hikers on their way down assured us that we’d find the hut at the end of the tree line. Sure enough, we reached the last of the trees and saw a small triangle poking out from the top of the horizon: “there’s the roof”, I excitedly shouted, fully aware that we had another 2km of exposed hiking before we’d reach it. The locals had put large red, plastic poles in the snow to mark the path, but we didn’t need them in the clear weather. About a half hour into the treeless section, we saw a talk, dark figure climbing quickly behind us: “Yuuki?”, we both wondered, realizing that our friend was well ahead of schedule. “Yuuki!”

The three of us climbed in high spirits, with Kanako and I shell-shocked that Yuuki had taken just 90 minutes to ascend an area that took us over 6 hours to complete. We arrived at the hut, greeted by two of the friendliest hut owners in Japan. “Welcome, you’re our first guests of the season!”. The husband and wife team enthusiastically gave us a tour and the rules. “The toilet is a separate building behind the hut,” explained the owner, “just climb over the 2 meter wall of snow”.

After checking in and rehydrating, the 3 of us journeyed up to the summit in case the weather turned foul overnight. There was well over a meter of snow all around, and most of the signposts were still buried. The wonderful marshes and wild flowers wouldn’t show themselves for another month or so, but we enjoyed the winter scenery. “Let’s watch the sunrise from this point,” demanded Yuuki, before racing back down to the hut for a long awaited dinner. We cooked up some noodles in the lobby, while the hut owner brought out an interesting contraption. A cylindrical, foot-long metal tube, with a diameter of about 10cm. We were each allowed one guess about its use, but were dumbfounded by the answer. “The villagers use it to catch salamander, a local delicacy.” Kanako and I quickly put two-and-two together: “so that’s what we ate last night!” I mistakenly heard sanshou uo the previous night when the minshuku owner had really said sanshouuo, which is Japanese for salamander.

We awoke well before dawn, cooking up some breakfast in the frigid lobby before heading back up to the summit, where we waited. And waited. And waited. There was a layer of cloud on the horizon, and we wouldn’t see the sun for a few hours. Kanako was cold, so she headed back down to the hut. Yuuki and I waited patiently, hoping for a gap in the clouds. Soon too, I started down, alone. I’d gotten about 50 meters away when I heard Yuuki shouting at me, waving his hands. I raced back up to the summit, wondering what all the commotion was about. Yuuki had spotted a kamoshika on a neighboring ridge, and I arrived just in time to see it tumbling down the steep slope.

Just as we arrived back at the hut, the sun decided to come out, illuminating Mt. Hiuchi directly in front of us. We packed our things, said goodbyes to the hut staff, and started our long journey over to Oze. Aizu-koma was kind to us on this lovely early May morning, and the hospitality of the people in Hinoemata village will not be forgotten. To this day, even though I’ve filled out my address in dozens of mountain huts, minshuku, and other places of accommodation, the only New Year’s postcard we’ve ever received from any place we’ve stayed has been from the Aizu-koma emergency hut. We vowed to come back here again to repay our thanks.