Two peaks stood between myself and the completion of the hallowed 100. The remaining duo are actually on the same ridge line, a mere two-day walk that I could easily tie together on a three-day weekend. Timing doesn’t always work out how you plan, however, and if there was any chance of finishing off the peaks before the arrival of the winter snows then I’d have to grab every available opportunity. So, preciously two weeks after coming down the jagged spires of Tsurugi-dake I was at the southern end of the alpine spectrum, attempting to knock off Tekari as a day trip.

This mission called for back-up, and my trusty companion Fumito came to the rescue. After running my plan by him he agreed to not only shuttle me to the trailhead but also to tag along on the agonizing climb. Instead of the drive from Shiojiri, I met Fumito at Toyohashi station in Aichi Prefecture, where he had been transferred to earlier in the year. Despite its proximity to the Minami Alps, it still took us several hours to navigate the rural roads leading to the trailhead at Irōdo. One we arrived it was a simply of matter of pitching the tent by the side of the gravel road and catching a few hours of shuteye before the early dawn would signal our departure for the formidable challenge.

We embarked on our expedition shortly after dawn under a thickening sky. The route weaved through an army of cedar trees lined up in marching formation. Each step brought modest gains in altitude, as the views started to open up the higher the path forged through the woodlands. Shortly before noon the cedar gave way to trees of the more deciduous variety, and the cool autumn air brought a tightening to my lungs that threatened to bring a premature end to our operation. I stopped briefly, sucking in large pockets of air deep into the lungs until the bronchial spasms subsided. I’d never had a problem with asthma before, so I needed to hurry up and finish these last two peaks before they finished me.

The lungs somehow returned to proper working order just as we reached the junction at Mt. Irōdo. We were now officially on the ridge that ran along the entire spine of the mountain range. The altimeter read 2500 meters: preciously 1700 vertical meters higher than our Toyota parked in the valley below. The two of us were absolutely spent from the exertion of energy, but the battle was far from over. Though the majority of the steeper bits were behind us, we still needed to tramp along a ridge laden with more ups-and-downs than most roller coasters. We each downed an carb-laced energy gel and a bag of mixed nuts and slowly glided through a wooded plateau affording views of Mt. Hijiri across the valley. The cloud had yet to invade my last remaining Hyakumeizan, but the barometer warned us that menacing weather was just around the corner.

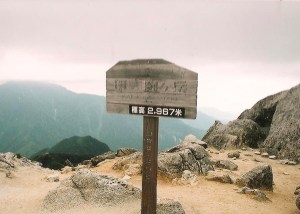

The pace slowed to a crawl as we followed a dry creek bed through an area ablaze with the yellows and reds of an early autumn. Just below the terminus of Mt. Izaru a small mountain spring brought refreshment to our dehydrated bodies, and by sheer luck the grade eased up just as the eaves of Tekari hut came into view. Peering over the edge of the southern ridge, the conical massif of Mt. Fuji punctuated a rolling torrent of boiling cloud, presenting a spectacle that surely would have had Hokusai glowing with delight. After chatting with the hut owner briefly, we topped out on Tekari’s tree-lined summit shortly before 3 in the afternoon. It had been one gargantuan effort to get there, and the majority of climbers would simply settle into the padded comforts of the cozy hut, but we both had work the following morning.

Clouds swept in from the east, providing a much-needed catalyst to get us moving back towards the junction. I tucked the camera away snugly in my pack, knowing that photo ops would only slow us down. We hit the junction at Irōdo a little past 4 and trudged back down into the dominion of evergreens just as the skies opened up. The canopy above kept most of the larger drops from soaking our gear as we limped through a network of downed, moss covered cedars and lumps of weathered granite. By the time we reached our automobile the first signs of dusk flickered through the forest. It was a monumental climb of nearly 12 hours that both of us vowed never to repeat. One thing was certain: the final peak would be knocked off at a much more leisurely pace.