The snow-capped perfection of Ontake’s curvy volcanic form was too much to pass up. Standing on the summit of Mt. Ibuki last month, my eyes were immediately drawn to the sacred peak. The snow cover was gently waning, and I’d be a fool to pass up the opportunity to scale the mountain before the onset of the rainy season. So in early June, I geared up for the train ride through Kiso Valley to Kiso-Fukushima, where I connected to the bus the popular trailhead of Ta-no-hara.

Except for a few locals who got off along the way, the bus was completely deserted. The route wound its way through a massive ski resort, whose grass-filled runs lay dormant, waiting patiently for the snow to return for another season of abuse. Halfway up the switchback-obsessed route, the bus passed by a hill-climbing cyclist, who pushed through the incredible ascent with apparently simple ease. Either he exercises for the pure joy of it, or he must be training for a upcoming race.

The upper half of Ontake’s majestic form sat in a thick blanket of cloud. Snow fields stretched from the concealed heights of the peak like a smudged Mondrian painting. A half a dozen elderly folks milled around the parking lot, unfastening gaiters from their early morning ascent. I guess most people are off the peak by late morning, but I knew my speed and fitness would not be a problem. It was the clouds I was worried about.

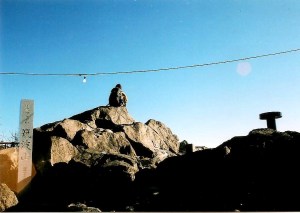

After a quick prayer at the shrine, I passed through the flatlands and onto the steep slopes of the volcano, passing by an impressive collection of Buddhist statues standing firmly among the pumice boulders and deep red soil. These works of art were placed in regular intervals among the straightforward route, a testament to the importance of this peak for ascetic monks. On this particular overcast day, the mountain was mysteriously absent of the white-clad pilgrims, who usually fill the peak during the busy summer months. Perhaps it was because the sacred structures flanking the summit plateau were still sleeping in their deep snow drifts of a lingering winter.

Somewhere around halfway up the long slog towards the 3000 meter mark, I heard footsteps quickly approaching from behind. As I turned around, I made eye contact with an energetic climber dressed in bicycle gear. It was the same cyclist I had seen on the bus ride up. Not only was he riding the hill to the trail start, but he was running up the mountain as well. Soon after passing me, we hit the first of many long snow fields, and it was here that the rain commenced. The athlete halted his footsteps and retreated, blurting out a quick “zannen” before vanishing back down towards the parking lot. My guess is that this climb is a weekly occurrence for him,and he wanted to hit the pavement again before the roads became too slippery. The rain didn’t stop me from advancing, however, as I forged a path up the gargantuan valley of snow until it disappeared into the mist.

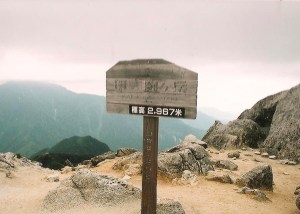

The rain only lasted about 10 minutes, letting up as quickly as it had come. I’m sure that cyclist was cursing his hasty decision, and I was half-expecting him to resume his hike, but I never saw him again. Once into deep cloud, the dirty white of the crusty snow meshed with the ghostly white of the clouds, and if it weren’t for the deep groove of footprints I never would have found my way to the ridge. Once at the summit of Otaki, the snow gave way to volcanic steam vents, which wore thick layer of sulfuric cologne. The shrine here was still buried up to the roof eves, but the final push to the summit lie on the wind-swept ridge, so navigation was a breeze except for the wafting aroma of rotten eggs attacking from all directions. The top of Ontake was home to yet more structures, which provide accommodation for arriving visitors, but only during the main climbing season. The doors were still boarded up, and the top lay deserted sans a few other hikers who had made the brave ascent in the dismal conditions. One such visitor stood out among the other elderly walkers: a young Japanese man out hiking along. Out of the two dozen Hyakumeizan I’d done so far, this was the first time (other than Mt. Fuji of course) to run into someone my age, so we immediately struck up a conversation.

He introduced himself as Fumito, a 24-year old originally from Kagawa Prefecture who had relocated to Shiojiri to work for Chubu Electric. I inquired about his choice of climbing routes, and it turned out he had started an hour earlier than me from the same approach: I very likely walked right past his car when disembarking the bus. Since I had no way of getting back to the station, I politely asked if he could honor my request. Gladly, he accepted, and both of us decided to descend together back down the same trail we had come up. My original intention was to traverse over to two small volcanic lakes lying just below the summit before making the long trek down to Nigorigo hot spring. There were two things inherently wrong with this idea: for one, I physically had no idea which direction the two lakes rested, since visibility in the thick fog was reduced to only a couple of meters. Second, the entire route on the northern face of the volcano was completely buried, with few hikers ever using that approach even in the summer season. I would surely get lost on the way down and even if I didn’t, I would have to negotiate some sort of ride out of the hot spring town.

Fumito and I talked the entire way down, finally popping out of the clouds into unexpected sunshine. I told him of my quest to climb the Hyakumeizan, which he enthusiastically endorsed. On the drive back to town, the skies opened up, dumping heavy rain that forced us to the shoulder of the road. Both of us praised our excellent timing, and I knew right then that I had made the wise decision not to do the traverse alone. Fumito dropped me off at Fukushima station, where we promised to go hiking again sometime soon.