My first visit to Kobushi, an autumn ascent under perfect skies, is one of the highlights of my Hyakumeizan quest. Usually the rule of thumb when reclimbing the Meizan is to never re-attempt a peak you had perfect weather on the first time around. However, my return to Kobushi is for another purpose – Saitama’s highest peak.

Had I been attempting the prefectural high points during my Hyakumeizan days then I would not have needed to return. You see, Saitama’s highest mountain, Mt. Sanpō, is just 10 meters higher and a short 30-minute climb from the summit of Kobushi. Instead of the popular trail on the Yamanashi side, I start from the Nagano village of Kawakami and the idyllic surrounds of Mōkidaira trailhead.

Naresh, Alekh, and I navigate the narrow farm roads through Kawakami shortly past midnight on a calm Friday evening. The torrential rains of the previous day have given away to fair skies and a bright full moon. We park in a corner of the large parking lot and settle into a fitful sleep: Naresh pitches his tent while Alekh and I cram into the trunk of the automobile. Cars continue to trickle into the parking lot throughout the night, robbing us of a chance of uninterrupted sleep. At 5am we spring to life, fueled by the fresh cups of chai and a light breakfast of bread.

The path starts out as a gravel extension of the forest road, through a flat section of track smothered in thick moss, an homage to the wet weather that typically blankets the Oku-Chichibu highlands. Thick clouds move swiftly through the strong gusts pushing through the troposphere, the last remnants of the typhoon now battering the east coast of Hokkaido. The muted morning light brings out the verdant greenery of the primeval forests – we point our lenses in all directions in order to capture the sheer beauty of the place.

We soon reach a junction for a trail that heads to Jūmonji-tōge, an alternative finish point should we choose to do the full 18km loop hike. We continue straight, sticking to the right bank of the swift-flowing waters of the Chikuma river, mesmerized by the crystal clear water and hypnotic hissing as the river pushes past large boulders and twigs. This is easily one of Japan’s most pristine sections of river, with absolutely no sign of concrete nor any dam intrusions to its natural flow. A pair of fishers wade in the river, casting their bait in search of succulent sweetfish.

The track is clearly marked and easy to follow as the three of us push on in unison, slowly upward toward the source of the river. Parts of the route remind me of virgin swaths of the Minami Alps, dotted as they are in a twisted network of larch, spruce and hemlock, all rising upward towards the bright sunlight now beginning to pierce the clouds above. Most hikers approach Kobushi from Nishizawa gorge, along a long, steep spur dominated by views of Fuji and the South Alps. Having done both, I can comfortably say I prefer this hidden entrance to Kobushi’s lofty perch.

After a couple of hours we reach the source of the Chikuma river, the start of a long journey to the northeast to the Sea of Japan, 367km to be exact. Upon entering Niigata Prefecture, the river name changes to the Shinano, which many will recognize as Japan’s longest and widest river. Here, at an elevation of 2200 meters, the water trickles out of an underground stream, with a plastic cup in place so that visitors can sample the cool, refreshing water. We fill up our water bottles and settle down on a toppled tree log for a snack and a quick perusal of the map. An 8-point buck (east coast counting system for ruminant aficionados) grazes in the forest just above, oblivious to our gazing stares. Seeing such stags in the wild is a surprisingly rare sight, as most deer just stick to the twilight and dusk hours for their meals.

From here the path steepens, but after a twenty minute push we top out on the ridge, the start of familiar territory as I had traversed this exact route during my first walk along the spine of Chichibu. Turning left, we glimpse a view of the top of Fuji before reaching the edge of a landslide where the views really start to open up. Just above it, the summit of Kobushi baths in the late morning sun, hikers resting behind their wide-brim hats and ultraviolet arm sleeves. It takes just 10 minutes to reach the summit, just as the cloud begins its daily rise to blot out the views. We gaze at Fuji briefly before a few summit snapshots and an additional snack. Mt. Sanpō sits on a steep spur to the north, its bulbous form sitting backstage as a stand-in to the main star Kobushi.

The track north immediately loses altitude through a pristine primeval forest of towering conifers, the broad track lined by a carpet of healthy ferns. After bottoming out the path starts the long, somewhat steep, climb to the top of Saitama. Between gasps for breath I use the GPS to gauge progress as we top out shortly before noon. In a celebratory mood, Naresh boils water for chai as we eat a filling lunch while admiring the abundant 6-legged creatures in flight. Despite the altitude, a swarm of dragonflies enjoy the wind gusts above the peak while a particularly persistent horsefly tests our patience.

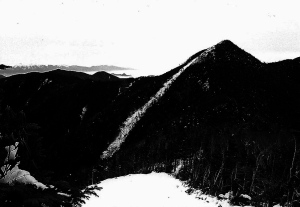

Feeling energized by the caffeine, we continue walking along the ridge, committing ourselves to the full loop. It seems like a breeze on the map, but the immediate loss of 200 vertical meters to the aptly-penned shiri-iwa, or big ass rock as we have nicknamed it, has us rethinking our decision. The next hour or so on the sabre-toothed ridge is certainly kicking our ass – perhaps the real origin of the shiri-iwa nomenclature.

We take turns overtaking a trio of gung-ho hikers who share our astonishment of the undulating nature of the route. At the junction just below Bushin Shiraiwa, a craggy peak now off limits to hikers, we pause to catch our breath and wipe the sweat from our brows. Naresh is starting to feel the contours in his knees, so as he straps on the knee braces we look over the remaining stretch of trek – just one peak separates ourselves from Jūmonji-tōge, a peak by the name of Oyama.

Oyama, as it turns out, lives up to its ‘big mountain’ moniker. While the climb is short but steep, the descent along the northern face is adorned with more chains than Flavor Flav, a tricky ordeal on weary legs. We lower ourselves gently down the near-vertical cliffs and finally reach the mountain pass and hut just before my bowels explode in a fit of rage. I had been holding back the inevitable ever since summiting Sanpō, and the 200-yen tip charge for the western-style toilet is perhaps my wisest investment of the day.

Worn out but by no means exhausted, the three of us once again garner up the energy for the final descent of the day. Compelled by a desire to reach the car, the pace is swift yet unhurried, and upon reaching the shores of the Chikuma river can we once again smile at the marathon effort required to scale Saitama’s highest peak. Most hikers break this loop up into two days by overnighting on the mountain, a wise choice considering our battered state.

With peak #45 safely off the list, I can now turn my attention to the mighty mountains of Hokuriku for the final duo of peaks on the highest prefectural 47 list.